When it comes to building a career or wealth, luck and hard work both have an impact.

This is something the greatest investor of all time, Warren Buffett, often talks about. He admits that his success is also a matter of luck. After all, he applied the same investing strategy as his mentor Benjamin Graham.

But Buffett achieved better returns because of when he started. Graham had to invest through the most treacherous times for securities, the 1930s. But Buffett admits he was lucky in more ways than that. In his 2014 annual letter, he said:

“Through dumb luck, Charlie [his business partner] and I were born in the United States, and we are forever grateful for the staggering advantages this accident of birth has given us.”

But what about hard work? Didn’t Buffett and his partner Charlie Munger also put in the work?

It’s the age-old discussion of luck vs hard work. What matters more? Do you need both? Can you still succeed without much luck?

In this article, we’ll look at two people who are highly regarded in their field. One experienced luck much earlier than the other. But they both succeeded at what they wanted to do.

Case study 1: The novelist who won a literary award after sending out the only copy of his first novel

At 28 years old, Haruki Murakami was watching a baseball game in 1978 in Tokyo, when he had a sudden thought: I think I can write a novel.

The idea came “as if something had come fluttering down from the sky, and I had caught it cleanly in my hands.”

On his way home, he bought some paper and a fountain pen and started writing. After closing his jazz club for the night, he’d sit at his kitchen table and write. He did that every night. But since Murakami never wrote stories his whole life, and he didn’t formally study writing, he had no idea what he was doing.

He experimented with various things. Eventually, he discovered his writing style by writing his first chapters in English and then translating them into his native Japanese. Doing that helped him simplify his thoughts and cut out all the fat from his prose.

When he finished his 30-or-so thousand-word novella, Murakami submitted it to an editor of a literary journal. It was the only copy of his manuscript. If his manuscript was lost or the editor rejected it at first glance, Murakami admitted he may not have written another novel again.

But Murakami ended up winning one of Japan’s prizes for fiction. This encouraged him to write his second novel. By the time his third novel came out, he decided to become a full-time novelist and he sold his jazz club.

Murakami’s books have sold in the millions while his short stories, like Tony Takitani and Drive My Car (which recently won an Oscar), have been turned into award-winning films.

Conclusion: Beginner’s luck followed by consistent work

Murakami’s first novella (which he later described as “immature” and even refused to sell outside Japan initially) won him an award and paved the way for his literary career.

Maybe it was his talent that let him win an award on the first try. Or maybe the award-giving panel was just drawn to his strange writing style, which contrasted against most of Japanese literature at the time.

But Murakami wouldn’t have been the writing icon he is today if he didn’t practice a consistent writing habit and improved his writing every time he published.

He wakes up at 4 am on most days and he writes until noon. In the afternoon, he trains for marathons and listens to old records. He’s back in bed with his wife at 9 pm. He does this every day with little variation.

Now, he releases a new novel, sometimes a 1000-page best-seller like 1Q84, every two to three years. Luck may have given Murakami a springboard. But his habits and consistent hard work kept him from falling.

Case study 2: The scientist who discovered the fastest-acting cure for malaria took 40 years to gain the recognition she deserved.

In the late 60s, Chinese soldiers in Vietnam were dying by the thousands. The culprit was malaria. And major government scientists failed to find an effective cure.

So the government looked into other alternatives. They pinned their hopes on Tu Youyou, a researcher at the Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Beijing.

Tu was in her early 40s when she discovered the cure. She would become 84 years old, more than 40 years later, before the world recognized her and awarded her a Nobel Prize in 2015.

To understand how hard Tu and her team worked, we can look at the sheer amount of samples they had to study.1 Source: NCBI Tu specialized in traditional Chinese medicine. So she and her team combed through ancient texts and old folk treatments for clues.

They also traveled to remote regions to collect certain plants. After months of tedious work, they collected over 600 plants and created a list of almost 2,000 possible remedies. They studied every possibility and narrowed down their list to 380.

Then they tested each of those remedies on lab mice, one treatment after another. Tu faced failure after failure, through hundreds of tests. They did that for two years. Nothing worked.

Feeling stuck and facing a dead-end, Tu decided to return to the basics. She re-read her findings, reviewed every test, and searched for clues about what she might be missing. She found her answer in an ancient text, written about 1,500 years ago.

Tu recalibrated her experiments. Finally, she created a cure. Now, they had to try it on live human beings to confirm its safety and effectiveness.

To top it off, Tu and two of her team members volunteered to test the cure on themselves. They were willing to put their lives on the line to find the cure.

They infected themselves with malaria and received the first dose of their own drug. Thankfully, it worked.

Conclusion: Consistent work followed by luck.

Tu started her research in 1969. But it wasn’t until 2000 when the World Health Organization finally began recommending her treatment as a defense against malaria. 31 years later.

Tu also had many disadvantages: She has no postgraduate degree, no academic positions, and no research experience abroad. She’s not someone you’d call lucky or privileged.

Yet she persisted with her work with almost no recognition. That’s not something many of us do.

When was the last time you felt like quitting because you didn’t receive encouragement? That’s how beginners quit midway; when they feel their work isn’t getting the exposure and recognition they “deserve.”

But Tu managed to consistently do good work despite all that. Her cure has since saved millions of lives.

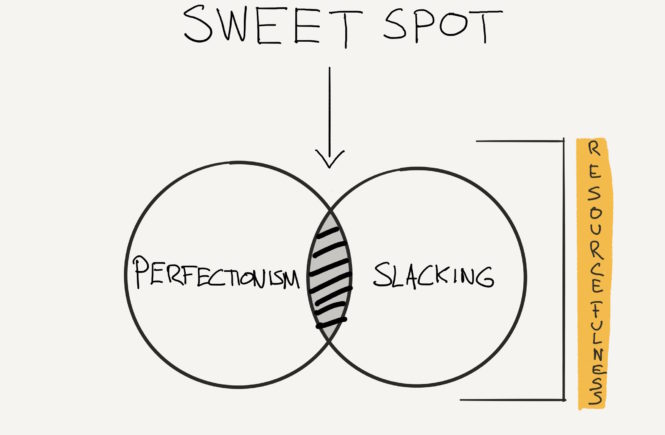

The effects of luck are often temporary

Anyone with a winning lottery ticket can become a millionaire. But lottery winners almost always lose all their money. They don’t know how to manage wealth. It’s the same with career success.

People who are given opportunities don’t become self-reliant. When they don’t get opportunities served on a platter, they struggle.

I think most of us are somewhere in-between Murakami and Youyou. We get sprinkles of luck here and there, usually a bit at the beginning and a bit in the middle.

In my own life, I’ve been lucky many times. I was lucky my parents moved to The Netherlands when I was one year old. I had the opportunity to get a good education here.

I was also lucky that some of my articles went viral within the first year of starting my blog. But other than that, my blog kept growing because of steady work.

The most important thing is to start. If you want to do something; write a book, create a business, work for a different company, and so forth — two things are important other than luck: Start, and keep going.

Everyone can start. But not everyone keeps going. The funny thing is that the people who keep going usually get lucky along the way. They just don’t know when. There’s only one way to find out.