When I think about psychotherapy and Sigmund Freud, I imagine a patient who’s reclined on a couch, with the therapist sitting out of sight at their head.

This is the view you often see in movies and media. The general perception of Freud is that he made sexual emotions the key to his philosophy. We assume that all our issues stem from some form of sex issue, which we’ve repressed.

Think about how people talk about the “Freudian Slip.” That’s when someone accidentally reveals their subconscious thoughts or desires through an unintentional slip of the tongue.

This happens when the unconscious mind overrides the conscious mind, resulting in a verbal slip that is often embarrassing or revealing in nature.

For example, if someone who’s been secretly attracted to their friend accidentally calls them by their ex-partner’s name, it could be considered a Freudian Slip. The slip-up may reveal the person’s unresolved feelings towards their ex and their true feelings towards their friend.

I never really read Freud because psychotherapy never attracted me. I can relate more to Alfred Adler, who focused on the person one wants to become in the future, instead of what has happened to someone in the past.

But I recently started to read more about Freud because I want to learn more about the history of psychology. If you want to learn more about his philosophy, I recommend reading Freud: A Very Short Introduction, by the psychiatrist Anthony Storr. It’s a great read.

What I found most interesting about Freud is his focus on self-analysis. Storr writes that Freud at some point turned the table on his patients:

“Instead of looking to the psychoanalyst for direct advice, positive suggestions, or specific instructions, patients had to learn to use psychoanalysis as a means of understanding themselves better. It was hoped that, armed with new insight, they would then be able to solve their own problems.”

Being able to solve your own problems is the only way you can move on. We’re independent and stubborn beings. We don’t like to be told what to do. We want to reach conclusions on our own. And Freud realized how to play into our nature, which made him help more people.

The complex mind

Let me give you a quick background. Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a method of treating mental illness that focuses on the unconscious mind and its influence on behavior.

He was born on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg, Moravia (now Příbor, Czech Republic), and later moved to Vienna, Austria.

Throughout his career, Freud developed several theories about the human psyche, including the concept of the unconscious mind, the Oedipus complex, and the idea of defense mechanisms. He believed that childhood experiences and repressed desires could shape a person’s behavior and emotions later in life.

Freud’s work revolutionized the field of psychology and greatly influenced modern-day approaches to treating mental illness. Despite the controversy surrounding some of his theories and practices, Freud’s legacy continues to impact the way we think about the human mind and behavior.

Freud emphasized the complexity of the human mind. He wrote:

“The mind is like an iceberg, it floats with one-seventh of its bulk above water.”

According to Freud, nearly all people have mental problems or “neuroses,” which come from unresolved conflicts between the conscious and unconscious mind.

Neuroses are often characterized by symptoms such as anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive behavior, and phobias.

Given the fact that almost every normal human being deals with some form of anxiety, Freud was right. He particularly warned people who pretend to be perfect:

“The more perfect a person is on the outside, the more demons they have on the inside.”

This is one of my takeaways from Freud: No one is perfect. We all have issues. That’s what makes us human. We’re simply complex beings.

Out of vulnerability comes strength

It can be easy to think our neuroses are a weakness. But in reality, understanding our mental blocks is the key to unlocking our full potential.

It starts with accepting that we have vulnerabilities. And that’s a good thing, as Freud said:

“Out of your vulnerabilities will come your strength.”

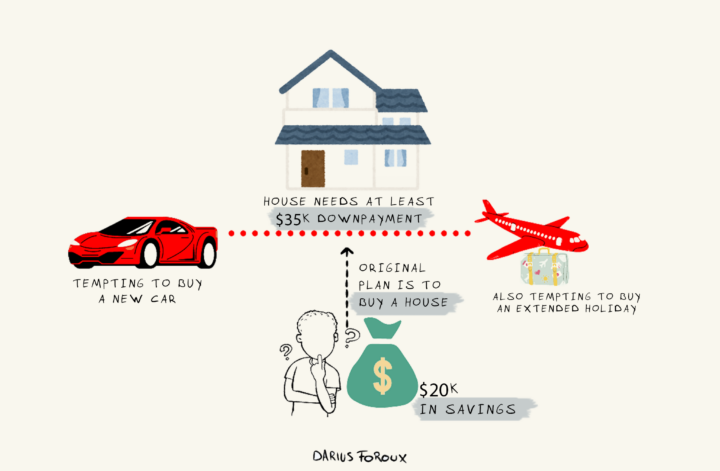

When we understand our weaknesses, insecurities, or sensitivities, we learn who we are. I firmly believe that your life starts when you start to truly learn more about yourself, AND accept everything you learn.

This is an ongoing process. I’m 36 years old and have been reading philosophy since I was 16. In the past 20 years, I’ve made a lot of mental progress. But I still learn new things about myself.

For instance, I always thought I was kind of adventurous. I traveled a bit and lived abroad a bit. But I was never 100% comfortable. I just liked the idea of getting out there and exploring the world.

In reality, I like to stay in my hometown, read, write, work out, spend time with family, friends, and strive to improve myself every day. My mission is to share my findings on living better with the world.

But I couldn’t come to this conclusion if I didn’t try. It’s important to remember that our past experiences and struggles have shaped who we are today. As Freud noted:

“We are what we are because we have been what we have been, and what is needed for solving the problems of human life and motives is not moral estimates but more knowledge.”

More self-knowledge is the solution to a better life.

Help yourself and help others to help themselves

My biggest takeaway from Freud is about the way he changed his treatment method. Instead of giving direct advice, he asked questions and allowed his patients to figure out their own problems.

Once we figure out our problems, we almost always know what we need to do. This is something I also learned early on at my jobs and in university.

The good managers and teachers I had never told me what to do. They hardly ever gave direct advice about personal things. For instance, when I worked as an inside sales agent at a bank, I remember my manager listening in on a call once.

He asked, “Why do you talk in the past tense? Why do you say, ‘Dear so and so, I was wondering if you had time to speak and so and so?’ Why do you think you use that language?”

I believed that I was interrupting people and wanted to be polite. He asked, “Are you really interrupting them or are you trying to help them with your offer?”

From that point, I changed my mindset and didn’t think I was interrupting clients. I was simply informing them. I had a great offer for a new credit card and wanted to tell them about it.

So I called people up and said, “Hi so and so, I’m calling you about our new credit card. Our clients love it. Do you want to hear more?” I instantly closed more deals.

Since then, I like to give feedback that way when I talk to someone 1-on-1. In my writing, I can be more direct because I don’t only talk to you, I also talk to myself. When you talk to yourself, you can be as direct as you want.

But I still keep in mind that I don’t want to tell people what to do. No one likes that. I just say, “Here’s what I do. And here’s why I do it.”

Just like this article. I use theory and examples to back it up. It’s not up to me to decide what others do with this information.

The most important thing is that you always help yourself. Learn more about yourself. Analyze your decisions and thoughts in your journal. Get to the root of your challenges. And then, ask:

“How can I improve?”

That way, you have the cause and you have a plan. Nothing can stop you now.